Foundational Thinking For Creating Good Behavior In Dogs Part 2 : Choose Your Methods of Training Carefully, Especially with Reactive/Fearful Dogs.

By Christine Mallar, Co-owner, Green Dog Pet Supply. Christine has 30 years of positive reinforcement training experience with dogs, cats and captive exotic animals.

There is still a big disconnect in the world of training – there are two camps: some trainers that  use positive reinforcement training (“Causing desire of a thing, situation or behavior by using a pleasant or motivating stimulus”), and some that use aversives (“Causing avoidance of a thing, situation, or behavior by using an unpleasant or punishing stimulus”).

use positive reinforcement training (“Causing desire of a thing, situation or behavior by using a pleasant or motivating stimulus”), and some that use aversives (“Causing avoidance of a thing, situation, or behavior by using an unpleasant or punishing stimulus”).

Humans and dogs are definitely different species with different perspectives in many ways (check out the book in the photo below). However, both dogs and humans have similar sorts of things that motivate us – things that might make us drag ourselves out of the comfort of our cozy beds to do something that we might not exactly choose to do for pleasure, but that are motivating for other reasons.

Check out Patricia McConnell’s book, “The Other End of the Leash” It’s a really interesting read on the differences between humans and dogs that often cause miscommunications.

1) Love – We might do tasks or favors for people or creatures that we love that then serve to strengthen our bonds and often cause them to show us affection or approval, which feels good.

2) Money – lets call it “currency”. Some of us are lucky enough to have jobs that mean something to us and reinforce our desire to be there, but let’s face it: When it comes to dragging ourselves out of that cozy cave and applying ourselves to tasks we might not choose to work hard on just for the fun of it, we’re all working because we get paid. For dogs, one of the most effective currencies is yummy treats. Learning is challenging for all of us – and for dogs it can be both physically and mentally challenging. It can also be emotionally challenging when we’re working on behaviors that will help them combat the discomfort or outright fears they might have about strangers or dogs or loud noises, etc. Yummy treats can make those difficult things easier, and the fact that they’re sprinkled though the activity fairly regularly and appear when they do the best job can be very motivating indeed to try harder to make that good thing happen. If only our salary could magically appear a dollar or two at a time, right when we do a good job with something or complete a task, or especially when we do something we don’t want to do. We might get more done and have more fun doing it! There’s science to this: Wikipedia says, “In popular culture and media, dopamine is usually seen as the main chemical of pleasure, but the current opinion in pharmacology is that dopamine instead confers motivational salience; in other words, dopamine signals the perceived motivational prominence (i.e., the desirability or aversiveness) of an outcome, which in turn propels the organism’s behavior toward or away from achieving that outcome.

3) Fear – Fear can be a pretty effective motivator for both humans and animals, but as we know, it comes with baggage. Anyone that’s had a relationship with a family member or supervisor that is someone who is overbearing, judgmental, explosive with their emotions or who is quick to punish or belittle you, knows that that kind of motivation can create a lot of anxiety. It can make you feel jumpy or withdrawn when they’re around and can make you desperately seek approval that you don’t generally get, which doesn’t feel good. That person might actually be pretty pleased with this result, not perceiving that it’s tearing you up inside, or that the relationship could be much more satisfying if it was based on mutual trust and admiration.

My opinion is that just because something might occasionally be effective, it doesn’t mean that it’s the best method. In fact, the biggest trouble with using aversives (besides the byproduct of eroding the relationship and the development of mutual trust) is that it’s a method that can have serious consequences when used to address behaviors that are a result of discomfort or especially fear-based behaviors.

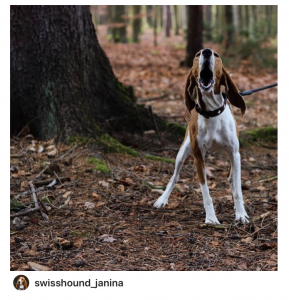

A good example of this is the use of choke collar “corrections” and shock collars for reactive dog behavior. Reactivity is a common problem we see in our store, when a dog lunges and barks at the sight of another dog. When a small dog does it, you’ll often hear the owner say that he thinks they’re bigger than they are or that the dog is always thinking that they’re the “alpha”. When reactive behavior happens with a big dog, they’re worried that they have a “dominant” dog or that their dog is being aggressive. There are of course many reasons dogs might have developed that reactive behavior. That little dog may have been carried for most of its puppyhood by a protective owner. I understand the urge to keep a tiny baby out of the jaws of a big dog that might think it’s something to chase and catch. But when that tiny dog gets to be a bit bigger and its owners then decide it should suddenly have to walk on a leash, that dog may be completely overwhelmed by the new situation, suddenly feeling very vulnerable and scared. A leash also keeps a dog from being able to run away, which means their only remaining tool to protect themselves and to tell the other dog to keep it’s distance is to bark at them. “Stay Back! Stay Back!” Sometimes owners will even push that dog closer to the bigger dog and tell it to “say hi”, which could completely overwhelm it, sending into defense mode and biting. This is not being “too big for his britches”, he’s terrified and may think he’s defending his life. The owners move to another part of the store and the little dog feels like his barking worked to end the situation.

In the case of the bigger dog, perhaps he didn’t meet tons of dogs when he was young and his owners thought the best way to “socialize him” was to bring him to the fenced dog park, where he met another dog with poor social skills, had a very scary scuffle and came out with some small wounds. He starts to bark at other dogs on walks, trying to keep dogs out of his space. It seems to work as the owner gets him out of the situation, but the owner is starting to feel very self conscious about her dog’s behavior. When she sees another dog coming, she says “Uh Oh” and her worry and agitation that it’s about to happen again is conveyed to her dog. She transmits all sorts of warning signals to her dog, gathering his leash tighter, feeling worried, inadvertently signaling to him that other dogs are indeed very bad. The dog starts to sound the alarm, the owner yanks him away and scolds him for his outburst, feeling embarrassed in front of the other owner.

he met another dog with poor social skills, had a very scary scuffle and came out with some small wounds. He starts to bark at other dogs on walks, trying to keep dogs out of his space. It seems to work as the owner gets him out of the situation, but the owner is starting to feel very self conscious about her dog’s behavior. When she sees another dog coming, she says “Uh Oh” and her worry and agitation that it’s about to happen again is conveyed to her dog. She transmits all sorts of warning signals to her dog, gathering his leash tighter, feeling worried, inadvertently signaling to him that other dogs are indeed very bad. The dog starts to sound the alarm, the owner yanks him away and scolds him for his outburst, feeling embarrassed in front of the other owner.

When the other dog is gone, the owner might feel and act relieved, and perhaps pet and comfort the stressed dog, feeling bad for having to punish his bad behavior. All of which tells the dog “We sure don’t like dogs. It’s so good and we’re so happy when dogs leave!” The other thing that’s happening here is that the sight of other dogs approaching starts to predict to the reactive dog that not only are we going to have to deal with a dog that I don’t feel comfortable around, but dogs make my owner upset too, and I’m likely to catch hell from her when dogs get close. “I MUST keep that dog away!” His discomfort around dogs starts to escalate, making the behavior worse.

Now consider adding pain to the equation. Prong collars and shock collars use a painful stimulus with the premise that the dog will make the association between the barking and the pain and stop barking. The trouble is, the real association for the dog that is made by the presence of the other dog is, “Dog approaches, I feel pain. Dog leaves, pain stops”. This can make a dog’s fear of other dogs spiral upward. This process can make dog reactivity escalate. The owner then has to keep escalating the punishment, which even if it does make the dog lessen his barking, it certainly will also continue to increase a dog’s hatred and fear of other dogs.

As an owner, you have to think, “What do I wish would happen when a dog approaches?” Don’t you wish that your dog would be happy and relaxed or indifferent when he sees another dog, or that he would at least pay attention to you instead of the other dog? A dog that has learned that pain and disapproval and anxiety are the only things that happen when other dogs are near will never be relaxed around other dogs.

However, a dog that has an owner that proactively avoids confrontations and creates safe space between her dog and others is a good first step. Then she might start to try and create positive associations for her dog about the sight of other dogs at a distance. She can start to pretend she feels happy when we see another dog at a distance far enough away that it doesn’t illicit that barking, and rewards that view of another dog with yummy treats. “Look! There’s a dog! Aren’t you lucky!” When the dog is out of view, the bar is closed. “Aw too bad! Dog’s gone. We’ll have to find another one!” She’s always looking out for opportunities to reward each time a dog is sighted (no matter what her dog’s behavior is like), managing his space to make sure he’s not too close, and stopping treats when the other dog is gone.

Why would she still “reward” when her dog isn’t acting perfect when he sees other dogs? Because she’s using “classical conditioning”. Classical conditioning is about creating an association. It’s a learning process that occurs when two stimuli are repeatedly paired – you all remember Pavlov. After he rang that bell, he then brought the food bowls. Very quickly the dogs started to drool when they heard the bell, before they ever saw the bowls coming. Bells would have never made a dog drool before that association was made. If you were to give a little boy a shock every time he saw a white bunny, it wouldn’t take long at all before the sight of a white bunny made him cry. He very likely would have a lifelong aversion even to a photo of a white bunny, even if as an adult his rational mind could understand that a white bunny probably wouldn’t hurt him.

Classical conditioning is a simple, very powerful method that can be used to change an animal’s (or a person’s) emotional response. This is what reactive behavior is all about: an involuntary emotional response that’s been developed because of the associations the dog has made between the sight of a strange dog and what it predicts will happen due to previous experience. This is how all living creatures learn, and it’s the reason that positive reinforcement training is entirely rooted in science and why it can be so powerfully effective in changing behavior in dogs.

We not only experience classical conditioning every single day, but we have all had experiences that show us that associations can be changed. Example: lets say every time my phone rings it’s terrible news. Someone breaks the news that my friend died. My boss is calling because I forgot I said I’d work today and she’s pissed. My doctor calls to say that lump needs a biopsy. My judgmental relative calls to “say hi” but spends the whole time complaining that I never call, and then criticizes my mother the way she always does. My vet calls and gives me bad news about Otis’ blood work, etc. When that phone rings, my heart sinks. “What is it now?” That heart-sinking feeling is not voluntary. It’s an emotional response to the sound of the ringing phone. Then, what if suddenly each phone call I get is great news? A long lost friend calls me and we reconnect and chat and laugh together. My vet called and said it was a mistake and Otis is actually fine. I get a call that my biopsy is benign. Someone calls saying they’ll buy the thing I posted for sale and I suddenly will have some cash in my pocket. The dream job I interviewed for is mine! Now each time the phone rings, I’ve started to have a little emotional lift in my chest, and a little intake of breath. “Ooh! Who can it be?” says my subconscious. I couldn’t have felt that happy little lift in my heart just because someone told me to. So, creating a positive association, over and over, with something that I used to feel uncomfortable with can truly change the way I feel about that thing. Now I don’t feel I have to swear when the phone rings, which brings us to the barking analogy: “If I feel that the presence of a dog predicts bad things, I will bark at it to keep it away. If I then feel (as a result of lots of repetition) that the sight of a dog at a distance predicts only good things will happen and I feel no threat to my safety, I will not feel the need to bark at it.” This clever owner will also use operant conditioning (rewarding a  good choice making it likely I’ll try to make that choice again and again) and reward that quiet dog when he could have barked and didn’t. She might also start to ask for behaviors that help him deal with the situation like “Watch Me” and reward those behaviors frequently. So, creating the simple association between “dog in view” and “cheese” can have powerful effects, and eventually that dog can be asked to be closer to other dogs and still be able to hold it together, gaining confidence around other dogs, becoming more relaxed in their relative presence, and also gaining confidence in his owner to manage his space. It works.

good choice making it likely I’ll try to make that choice again and again) and reward that quiet dog when he could have barked and didn’t. She might also start to ask for behaviors that help him deal with the situation like “Watch Me” and reward those behaviors frequently. So, creating the simple association between “dog in view” and “cheese” can have powerful effects, and eventually that dog can be asked to be closer to other dogs and still be able to hold it together, gaining confidence around other dogs, becoming more relaxed in their relative presence, and also gaining confidence in his owner to manage his space. It works.

So this is why positive trainers get so upset when they see someone like Cesar Milan or other dominance based trainers “training” a reactive dog: They almost exclusively use punishment with reactive dogs and they see every undesirable dog behavior through the lens of “dominance” or “alpha” behavior. Not only do positive reinforcement trainers know there are other methods that aside from being kinder, can also help to change their dog’s perception of the stimulus, but they realize that punishment can create a greater negative association with the stimulus than they even had before. Remember, someone’s fear of spiders isn’t a voluntary reaction, and no amount of shoving spiders into their  face, or slapping them when they see a spider will help at all to make that fear of spiders go away, even if they can learn to suppress their screams to avoid a slap. It will only work to deepen their agitation about a spider’s presence. (And there will always be a distinct possibility that the sudden sight of a spider will make them scream anyway if they’re unprepared).

face, or slapping them when they see a spider will help at all to make that fear of spiders go away, even if they can learn to suppress their screams to avoid a slap. It will only work to deepen their agitation about a spider’s presence. (And there will always be a distinct possibility that the sudden sight of a spider will make them scream anyway if they’re unprepared).

Cesar Milan and the skateboard

My favorite illustration of how his method is faulty: I watched a show of his where an English Bulldog was very reactive when he saw a skateboard, barking and lunging and biting at it. He put on a choke chain and had a kid roll by on a skateboard while his owners looked on. When the dog started to bark, he kicked the bulldog. He said he wasn’t kicking him, he was just distracting him using his foot. It was enough force to move an English bulldog sideways which makes me feel like you’d call it kicking, but maybe that’s just me. Anyway, he continued to “distract him with his foot” and then give a hard yank on the choke chain each time the kid rolled by. His timing was excellent, so the bulldog quickly learned that barking predicted kicking and choking, and he suppressed his barking, even when Cesar made the kid roll very closely by. The bulldog still looked distressed, and if a bark slipped out, he got a harsh correction. The owners were so impressed and praised Cesar’s amazing skills – the skateboard was right there and he wasn’t barking, in just a few minutes time! Then the owners had a try, and predictably their corrections weren’t as strong, and the dog barked. He was predictably flipping out at the skateboard’s presence. Cesar chastised them and said they had to show more dominance.

Every person and dog has a threshold at which they can contain themselves in the face of something horrible, but there will always be a level at which you cannot keep it together. A dog that is staying quiet because they’ve learned there’s a risk of punishment and pain is doing the equivalent of pressing his hands over his mouth, keeping himself from barking, but his opinions have certainly not changed about skateboards. The trouble is, the level of punishment has to escalate to regain the silence if the animal’s threshold is crossed. His feelings when he sees a skateboard have likely spiked into even greater levels of bad. The most important thing to point out is that this is a dog who will never ever be reliable in the

What if he learned to love skateboards like Tillman?

face of a skateboard that zooms by in real life. When that family’s 4 year old insists on holding the leash (as they do) and a skateboarding teenager appears from nowhere, that strong dog will likely react and inadvertently drag that child causing injury. No attempt has been made to make that dog feel comfortable around skateboards. If that family bought a skateboard and slowly associated it with all good things, teaching the dog that not only are skateboards safe to be near, but they actually predict that awesome things happen for bulldogs, that dog could become safe and reliable around skateboards, and that 4 year old could be holding the leash when he sees one. Positive reinforcement wins in this scenario. It may not create a sudden appearance of fixing a problem in 5 minutes like on the TV show, but it is far more likely to truly fix that skateboard problem for a lifetime, no matter who’s holding the leash.

Dominance and wolves

Trainers that use punishment often insist that just about every undesirable dog behavior can be attributed to their yearning for status, and that dominance is the underlying motivator for their actions. They have been led to believe that because they descended from wolves, that they must be in constant competition with members of their pack. The big trouble with this is that wild wolves don’t behave this way. There was a study in the 1930s that was reproduced a number of times by others that put unrelated adult wolves together in an artificial captive situation and discovered that they did indeed fight violently. Wild wolves are found in smaller family groups consisting of mated pairs and their offspring who stay in the group for several years. Sometimes families that know each other will come together for a time when resources are plentiful, and perhaps split up again when prey is scarce. When adolescents mature, they’ll leave the family to make their own. The only constant members of the group are the mated pair. It’s very unnatural to confine adult, unrelated strangers in a small captive setting, and this is a recipe for constant fighting and competition for resources.

Trainers that use punishment often insist that just about every undesirable dog behavior can be attributed to their yearning for status, and that dominance is the underlying motivator for their actions. They have been led to believe that because they descended from wolves, that they must be in constant competition with members of their pack. The big trouble with this is that wild wolves don’t behave this way. There was a study in the 1930s that was reproduced a number of times by others that put unrelated adult wolves together in an artificial captive situation and discovered that they did indeed fight violently. Wild wolves are found in smaller family groups consisting of mated pairs and their offspring who stay in the group for several years. Sometimes families that know each other will come together for a time when resources are plentiful, and perhaps split up again when prey is scarce. When adolescents mature, they’ll leave the family to make their own. The only constant members of the group are the mated pair. It’s very unnatural to confine adult, unrelated strangers in a small captive setting, and this is a recipe for constant fighting and competition for resources.

As David Mech stated in the introduction to his study of wild wolves (Mech, 2000), “Attempting to apply information about the behavior of assemblages of unrelated captive wolves to the familial structure of natural packs has resulted in considerable confusion. Such an approach is analogous to trying to draw inferences about human family dynamics by studying humans in refugee camps. The concept of the alpha wolf as a ‘top dog’ ruling a group of similar-aged compatriots (Schenkel 1947; Rabb et al. 1967; Fox 1971a; Zimen 1975, 1982; Lockwood 1979; van Hooff et al. 1987) is particularly misleading.”

As a zookeeper and conservation worker I’ve worked with and observed many species in captivity and in the wild who live in what you might call dominance hierarchies, and I can assure you that outside of the military, dominance doesn’t take the form that many trainers envision, with small infractions constantly punished aggressively, and lower ranking individuals constantly picking fights to rise in rank. Dominance theory is so poorly misunderstood by humans (who are all too often not skilled in reading dog communication). They might completely misinterpret things like appeasement behaviors (like jumping up to lick) as being an example of a dog misbehaving because it hasn’t been shown who’s boss. What is almost certainly happening is that they have no idea that anything else is being asked of them but to greet enthusiastically, and they’re actually showing deference (defined as humble submission and respect) by trying to lick your face. They just haven’t been taught that you’d rather they sit to greet, and that doing the new behavior can be very rewarding and result in the affection they crave.

I love this passage from Jean Donaldson’s book, Culture Clash, “My favorite myth is going through doorways first. What silly person came up with the notion that a dog would understand, let alone exert dominance, by preceding his owner out the front door? When dogs are rushing through doors, mustn’t we first rule out that they are trying to close distance between themselves and whatever is out there, as quickly as possible, because they are excited, because they are dogs, and because they have never been presented with a reason not to?”

through doorways first. What silly person came up with the notion that a dog would understand, let alone exert dominance, by preceding his owner out the front door? When dogs are rushing through doors, mustn’t we first rule out that they are trying to close distance between themselves and whatever is out there, as quickly as possible, because they are excited, because they are dogs, and because they have never been presented with a reason not to?”

In my next installment, I’ll address the concern that some people have that if you use treats that you’ll always have to use treats, every day, for every behavior. I assure you, though treats can still come in handy in some instances, there are many ways to control a dog’s valuable resources, making him earn what he wants in life by doing what you ask, right away.

Resources

One of the best little books ever about how to work with dogs who are reactive on leash is called “Feisty Fido” by Patricia McConnell PhD and Karen London, PhD. It’s a silly name but a fantastic book that walks you through the process and gives you good “What if” scenarios. It’s a very short read, but thorough enough to really help you. We have it at the store or you can find it here: https://www.dogwise.com/feisty-fido-help-for-the-leash-reactive-dog-2nd-edition/

Locally, we’re lucky to have one of the best trainers around (and the first Certified Behavior Consultant (CBCC-KA) in Oregon) right near the store. Call on Doug Duncan at Doggy Business – you’ll see a link for Private Training for Aggression on the front page at https://www.doggybusiness.net/

This article is part of a series of articles designed to help you train your new dog:

Congratulations On Your New Puppy! (or adult dog)

What a fun time you’ll have! We very much want your new baby to live a long, healthy, happy life, so we thought we’d compile some of the nitty-gritty dos-and-don’ts of puppy care. Socialization, nutrition, our favorite chews, tips on potty training, etc!

Raising a Puppy (Or Any New Dog) During Covid 19

All of us feel frightened and unsure of how long we’ll be living in this strange, suspended, frightening reality. A new dog is not just a delightful distraction from boredom- that little soul can really be a life raft for your psyche. But, this new-puppy-during-quarantine situation does come with a few unique challenges. How to work on socialization and help to prevent separation anxiety once you go back to work.

What Do They Want? How Should They Get It? (Foundational Thinking For Creating Good Behavior in puppies and kittens! Part One) Often we hapless humans try our best to tell our puppies (and kittens) what we want them to do or especially not do, yet the bad behaviors increase and we struggle to get them to be what we wish they would be, especially when it comes to attention-getting behaviors. I’m here to offer a few rules of thumb for most any behavior you don’t like.

Do I Always Have To Use Treats? (Foundational Thinking For Creating Good Behavior In Dogs Part Three) A lot of people worry about training with treats.

* Do I have to keep giving them treats for everything for the rest of their lives?

* Aren’t I bribing them?

* I want them to do things because they want to please me.

* I want them to do things right away and I don’t want to have to show them a treat to get them to listen.

These are all good questions. Here’s how to help your dog be able to do what you ask of them the first time you ask, while continuing to build a good relationship.

Drop It!

We’re continuing our puppy series with discussions of common training challenges. It’s so easy to accidentally create a dog that runs away from you when they get a hold of something they shouldn’t have. Wouldn’t you rather they spit something out of their mouth when you approach? You can do it!

Come!

The “Come!” command is one of the very most important things we can teach our dog. A reliable recall is imperative to get them quickly to safety, to recover them if they happen to get out the door, and to proactively remove them from a situation at the dog park that might evolve into trouble. It’s also a wonderful luxury when you are in a safe quiet place to be able to have your dog off leash and know you can get him right back when you want to. Like the command “Drop It!”, it’s easy to accidentally make mistakes when training this behavior that can undermine your success. Here’s how to succeed in training a reliable recall.